Recordings of classical music traditionally represent about 5 percent of all recordings sold. Of that 5 percent, I would guess that historical classical recordings are in the vicinity of 5 percent. That is, 5 percent of 5 percent.

I'll confess to a preference for relatively modern recordings (say, from the 1980s on), with a slightly guilty extra pleasure in sonic state-of-the-art discs. I'm easily seduced by the audiophile labels: the American Reference Recordings and Telarc, the Swedish BIS, the English Hyperion and Chandos, the Dutch Channel Classics. There are those who would say I'm trading sound for performance quality, and in a few cases (though certainly not all), they're right. They'll say I'm missing out on some truly extraordinary performances from earlier years, and they're right.

There's a legitimate case for a bias in favor of very good modern recordings. Music, after all, at its most basic, is sound. It's more than that, of course: elaborate relationships of different sounds. But, even considering only classical orchestral music, if you do not hear something close to the actual timbre of the instruments, the variable tone colors that players can produce, you are not truly hearing the music.

That's doubly true for the compositions of superb orchestrators like Mahler, Richard Strauss, and Ravel. In a drab, flat recording, you don't hear the full measure of sensuousness, resonance, tingling, menace, drone, chant, purr that an orchestra can produce and a talented conductor can tease or urge from his musicians.

Still, I cherish many recordings from the greats of earlier generations -- Bruno Walter, Pierre Monteux, Walter Klemperer, Herbert von Karajan, and others. (What about Toscanini, you ask. Sorry, for me he doesn't make the cut, although it's possible the sound of his RCA recordings, universally acknowledged to be dry and hard, could be a factor.) Their performance styles tended to be more varied and individualistic than those of today's international-minded, jet set conductors. (Globalization is as much a phenomenon in the arts as in economics.)

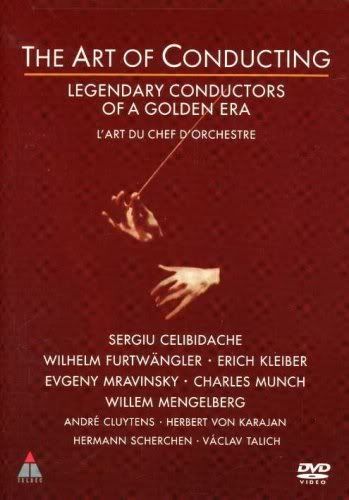

Videos of "old master" conductors, unlike sound recordings, are thin on the ground. Curious to see what a DVD set subtitled "Legendary Conductors of a Golden Era" offered, despite my loathing of the hype words "legendary" and "Golden Era," I borrowed the release from Netflix. Well, to be precise, half of it; for some reason, Netflix provides only one disc out of a two-disc set.

Three of the conductors on the available disc, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Evgeny Mravinsky, and Sergiu Celibidache, are cult figures. The others -- Willem Mengelberg, Erich Kleiber, and Charles Munch -- still have a solid reputation among the cognoscenti, but are marginal even among most classical music listeners. I had heard one recording led by Mengelberg and have one or two by Furtwängler, Mravinsky, and Munch in my collection. All I knew about Erich Kleiber I read in a detective novel by Nicolas Freeling: Kleiber's cemetery memorial has inscribed on it only his name and the musical symbol that means "rest."

The DVD is admirable. It includes long performance segments -- in contrast to the PBS talking-head style of musical documentary, where you get a 30-second snip of performance and then three minutes of an expert telling you how wonderful what you heard, or didn't hear, was. The sound quality of most of the sessions is good for their respective ages. The oldest are of Mengelberg conducting the Concertgebouw of Amsterdam in 1931 and the Berlin Staatskapelle a few years later.

It occurred to me that in both of these accomplished ensembles, at least a third of the musicians must have been Jewish. Within a few years, they would not be permitted to perform professionally. Eventually, no doubt, some of these men and women (yes, there are women visible among the players, and not just the harpists) who turned dots and lines on paper into glorious, inspiring sound would be shipped off to slave labor and death camps.

This video includes a session in which Sergiu Celibidache, the Romanian conductor, leads the Berlin Philharmonic in 1947. I'm inclined to see the hand of God in this being filmed and preserved. Celibidache conducts an electrifying Beethoven Egmont, but that's not what will stay most in my mind.

He and the orchestra perform in, literally, a ruin. It might be the remains of a factory, or maybe all that was left of the Philharmonie, Berlin's premier concert hall, destroyed in an Allied bombing raid in 1944. (Unfortunately, when you rent a DVD from Netflix, you don't get the notes that were included with the original packaging.)

The podium consists -- I'm serious -- of rubble with a square of wood atop it.

It looks like a concert at the end of the world. Nevertheless, you wouldn't know it from the conductor.

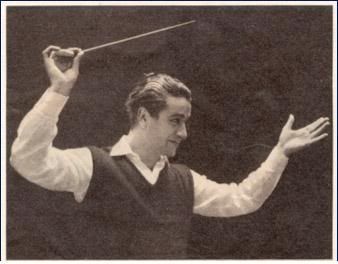

He inhabits his role to perfection. Later he would become (as the video shows in later segments) chubby, then corpulent, but in 1947 when there wasn't a lot of food to go around in Berlin, he was slender, his face bony and handsome. When he waves the conductor's wand and tosses his head dramatically, curly strands of hair swing over his forehead, Jerry Lee Lewis–style. If this was the beginning of the Celibidache cult, you can understand why he captured attention.

Some would complain, and probably did at the time, that playing the part of the ultra-well-dressed gentleman, what the English call a "toff," was in bad taste. Berlin had gone through a dozen years of Nazi rule, six years of war, three of regular bombardment, followed by a Red Army storm of rape and pillage. What was left of the city was still full of beggars, the crippled, the hungry.

I don't know what was in Celibidache's mind, but I suspect he knew exactly what he was doing. He was attired as someone in his position would have been before the continent went mad. He was bringing to life noble and affirming music, for an audience who — whatever their sins before and during the war might have been — felt it worth their while to cross the twisted and heaped wreckage of Berlin, perhaps spending money they could ill afford to attend the concert, so they could hear again what the human race is capable of at its best.

Like Beethoven whose music he set soaring, Celibidache was shaking his fist at the thunder and lightning. He was saying in music's wordless but profound language: civilization is unquenchable. The forces of evil shall have no dominion. They can unleash the horrors of war. They can kill artists. They can kill anyone. But they cannot kill this.

In our time, which many of the more alert are comparing with the 1930s, Celibidache's gesture is no small comfort.

He and the orchestra perform in, literally, a ruin. It might be the remains of a factory, or maybe all that was left of the Philharmonie, Berlin's premier concert hall, destroyed in an Allied bombing raid in 1944. (Unfortunately, when you rent a DVD from Netflix, you don't get the notes that were included with the original packaging.)

The podium consists -- I'm serious -- of rubble with a square of wood atop it.

It looks like a concert at the end of the world. Nevertheless, you wouldn't know it from the conductor.

Sergiu Celibidache

Celibidache is dressed au galant. He would have looked perfectly at home at the head of an orchestra before the war -- the war, the 1914–1918 one that kicked off Europe's descent into the abyss. He's turned out elegantly tailored in the traditional 19th century swallow-tail coat, with a contrasting light waistcoat; white pocket handkerchief; wing-collared shirt; striped tie; cuff links.He inhabits his role to perfection. Later he would become (as the video shows in later segments) chubby, then corpulent, but in 1947 when there wasn't a lot of food to go around in Berlin, he was slender, his face bony and handsome. When he waves the conductor's wand and tosses his head dramatically, curly strands of hair swing over his forehead, Jerry Lee Lewis–style. If this was the beginning of the Celibidache cult, you can understand why he captured attention.

Some would complain, and probably did at the time, that playing the part of the ultra-well-dressed gentleman, what the English call a "toff," was in bad taste. Berlin had gone through a dozen years of Nazi rule, six years of war, three of regular bombardment, followed by a Red Army storm of rape and pillage. What was left of the city was still full of beggars, the crippled, the hungry.

I don't know what was in Celibidache's mind, but I suspect he knew exactly what he was doing. He was attired as someone in his position would have been before the continent went mad. He was bringing to life noble and affirming music, for an audience who — whatever their sins before and during the war might have been — felt it worth their while to cross the twisted and heaped wreckage of Berlin, perhaps spending money they could ill afford to attend the concert, so they could hear again what the human race is capable of at its best.

Like Beethoven whose music he set soaring, Celibidache was shaking his fist at the thunder and lightning. He was saying in music's wordless but profound language: civilization is unquenchable. The forces of evil shall have no dominion. They can unleash the horrors of war. They can kill artists. They can kill anyone. But they cannot kill this.

In our time, which many of the more alert are comparing with the 1930s, Celibidache's gesture is no small comfort.

No comments:

Post a Comment